Los mapas en papel son planos, las pantallas en las que vemos Google Maps también lo son. Y nadie duda de su admirable exactitud. En cambio, nos dicen que la tierra es redonda… sospechoso, ¿no? ¡Hemos vivido en una mentira toda la vida! Ellos nos engañan.

¿Pero quiénes son ellos?

Los mapas, naturalmente.

Porque resulta que la Tierra no es plana, pero tampoco es perfectamente redonda, y comprender cómo describimos su forma es el primer paso para entender la cartografía moderna, la navegación o el funcionamiento del GPS.

La Tierra es una realidad única, pero existen distintos modelos para representarla: desde su superficie real, hasta los mapas planos que utilizamos a diario.

La superficie real: el planeta tal como es.

La forma más evidente de la Tierra es su superficie física: montañas, valles, océanos, mesetas y fosas abisales. Esta superficie es extremadamente irregular. Basta pensar en el relieve de los Alpes, el Himalaya o las dorsales oceánicas para darse cuenta de que describir el planeta tal como es resulta impracticable para cálculos globales.

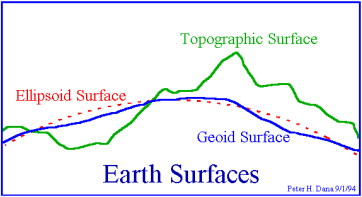

Aunque esta superficie es la que habitamos, es demasiado irregular para medir posiciones, distancias o trayectorias a escala planetaria. Para ello necesitamos modelos simplificados, más abstractos, pero mucho más manejables.

El geoide: la Tierra definida por la gravedad.

Imaginemos que pudiésemos hacer desaparecer todo el relieve hasta que toda la superficie de la tierra quedase a la misma “altura del mar”: nos habríamos librado de los accidentes geográficos. Entonces, ¿ya tendríamos una esfera perfecta?

No exactamente.

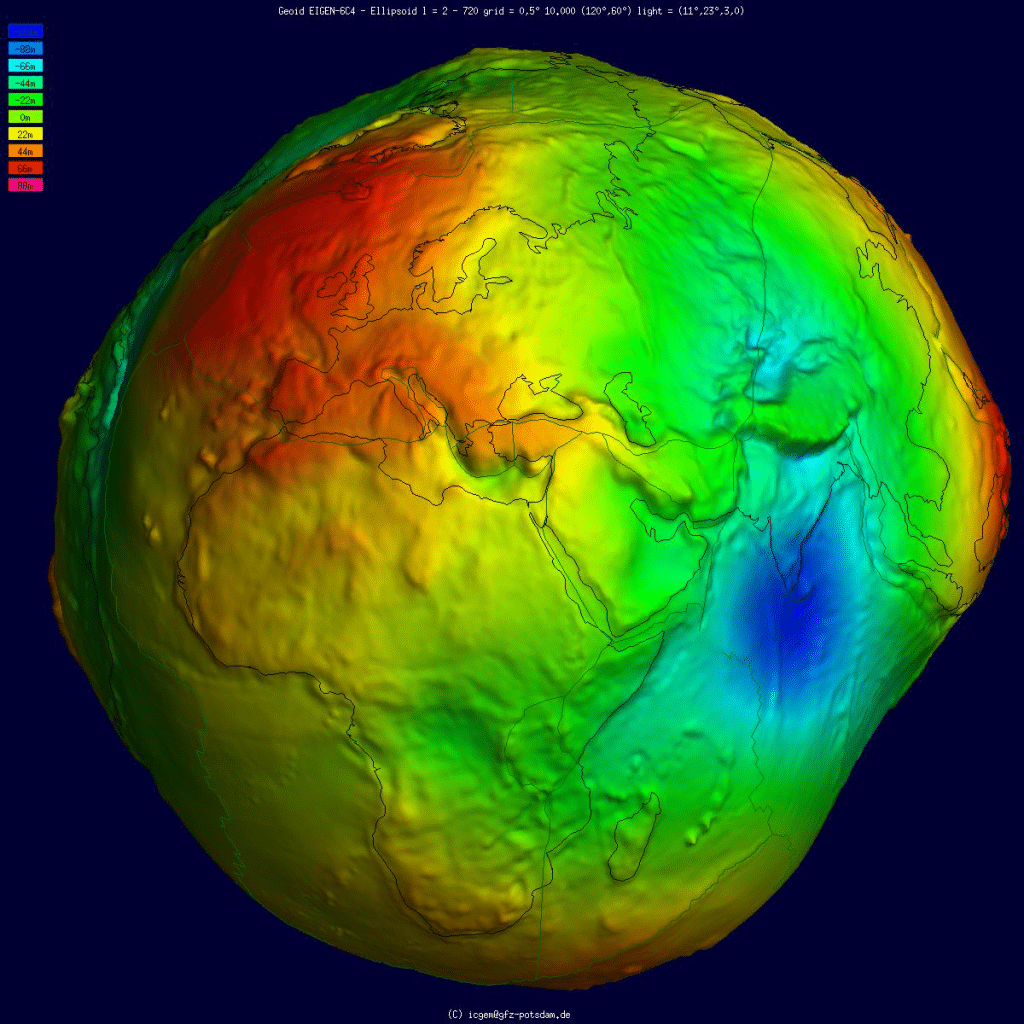

La forma que obtendríamos es el geoide, una superficie teórica definida por el campo gravitatorio terrestre, que no es una figura regular. Está ligeramente deformada debido a variaciones en la densidad interna de la Tierra y a su rotación.

Aún así el geoide es un modelo fundamental porque nos proporciona una referencia física muy importante: el cero de las alturas.

Representando estas irregularidades de forma muy exagerada, la Tierra sin montañas aún tendría la forma de… un buñuelo:

El elipsoide: una aproximación matemática eficaz.

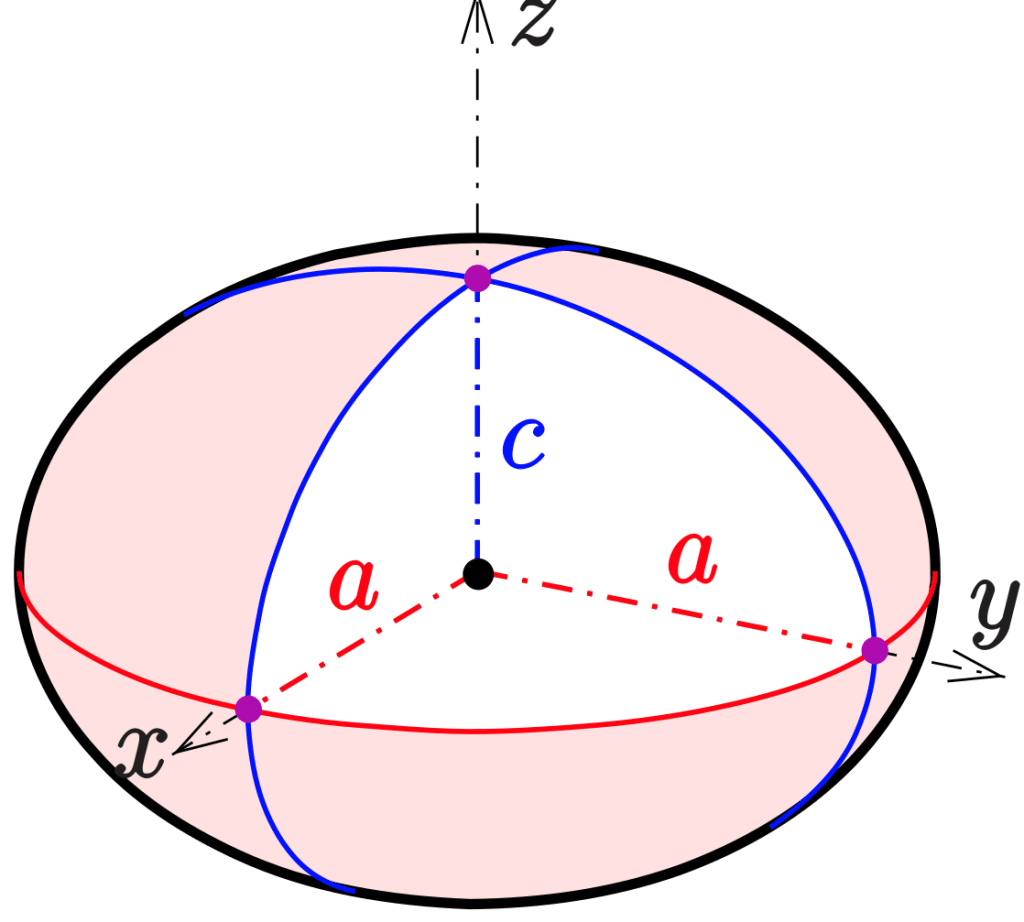

Por suerte, esta «buñuelidad» de la Tierra es mucho más sutil de lo que sugieiere la imagen. En la práctica, el geoide se puede aproximar por una forma matemática mucho más simple sin introducir errores significativos, lo que permite trabajar con coordenadas de forma precisa y consistente: el elipsoide de revolución.

Este modelo matemático se obtiene al girar una elipse alrededor de uno de sus ejes,

dando lugar a una forma ligeramente achatada por los polos. O quizá deberíamos decir ensanchada por el ecuador, ya que esta deformidad se debe a la fuerza centrífuga producida por el planeta girando sobre sí mismo.

La deformación es de poco más del 0,3%, pero sobre un radio de unos 6400 km supone más de 20km de diferencia.

Así que, si quisieras hacer un agujero hasta el centro de la Tierra, tendrías menos trabajo si empezaras a cavar desde el polo norte.

El elipsoide tiene una enorme ventaja sobre el geoide: puede describirse mediante ecuaciones matemáticas sencillas. Gracias a ello, podemos definir posiciones mediante un par de números: latitud y longitud.

Estos dos números deberían bastar para dar la posición de forma clara y repetible, ¿verdad?

Pues no exactamente. En la actualidad, los sistemas de posicionamiento por satélite utilizan elipsoides globales muy bien ajustados a todo el conjunto del planeta, pero históricamente existían (y aún se usan) distintos elipsoides regionales ajustados a una sección de la Tierra, y/o medidos en épocas pretéritas con mayor o menor precisión.

Datums: situar el elipsoide sobre la Tierra

Así que no siempre se aproxima la forma real de la Tierra con exactamente el mismo elipsoide. Por eso es necesario explicitar cómo encajan esos elipsoides unos respecto a otros. Aquí entra en juego el concepto de datum.

Un datum define la posición, orientación y escala del elipsoide. Durante muchos años, distintos países utilizaron datums propios, optimizados para su territorio. Hoy en día, los sistemas modernos tienden a emplear datums globales, compatibles con satélites y sistemas internacionales.

Cambiar de datum no significa que un punto se mueva físicamente, sino que cambian sus coordenadas numéricas al usar otro marco de referencia: El mismo punto real se expresa en coordenadas ligeramente distintas si se usan elipsoides ligeramente distintos.

dfasd

El error puede ser de unos centenares de metros, y hacen que los datos no casen. Si quieres dar un par de coordenadas de forma completa, tendrás que dar también su datum, lo cual determina el marco de referencia.

De una Tierra curva a un mapa plano.

Ya tenemos una superficie curva bastante sencilla, que representa la Tierra con suficiente precisión. Pero los mapas que usamos son planos.

Y pasar de una superficie curva (el elipsoide) a una plana siempre implica deformaciones, así que implica necesariamente mentir, perder alguna propiedad de la realidad por el camino.

Una proyección cartográfica es una transformación matemática entre el elipsoide y una superficie plana, como un cono o un cilindro. Cada proyección conserva unas propiedades y sacrifica otras, de este modo se escoge la proyección según las propiedades que conserve en función de la actividad que estemos realizando: el rumbo si estamos navegando, o la superficie si estamos cobrando impuestos. Por eso existen tantas proyecciones distintas, cada una diseñada para un propósito concreto.

Cuando vemos un mapamundi rectangular, no estamos viendo la Tierra tal como es, sino una transformación matemática que permite representarla en dos dimensiones para algún propósito concreto.

Google Maps popularizó una proyección que no conserva bien ninguna propiedad geométrica, pero que resulta visualmente familiar y computacionalmente eficiente, es decir barata de calcular, lo cual servía a sus propósitos. Por eso, ha acabado siendo el estándar de los mapas digitales.

En esta web se puede ver cómo la proyección usada en los mapas web magnifica las áreas a medida que nos acercamos a los polos: https://thetruesize.com/

Transformaciones: conectar sistemas distintos.

En la práctica, trabajar con mapas y coordenadas suele implicar transformar datos entre distintos sitemas:

- de un datum a otro,

- de coordenadas geográficas a proyectadas,

- o entre proyecciones diferentes

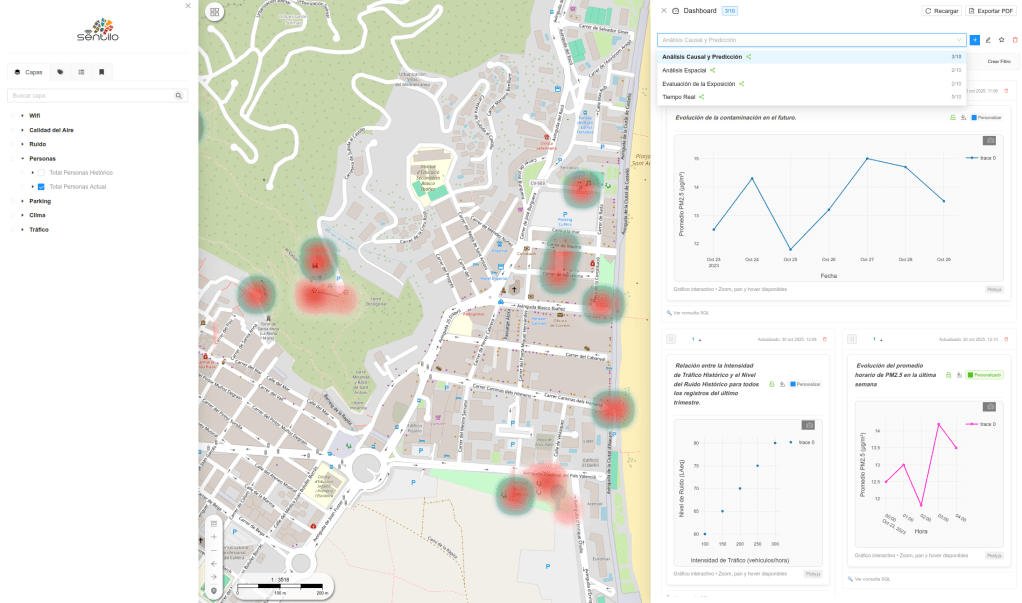

Estas transformaciones están perfectamente definidas y permiten que datos procedentes de distintas fuentes san compatibles entre sí.

Gracias a ellas, un punto medido con GPS puede aparecer correctamente en un mapa topográfico histórico, una imagen satelital o un mapa web.

Una representación, no una simplificación ingenua

Los mapas no niegan la curvatura del planeta; al contrario, son el resultado de siglos de trabajo para representar sobre un papel una Tierra compleja de la forma más útil para un propósito determinado.

Entender conceptos como superficie real, geoide, elipsoide, datum y proyección nos permite mirar los mapas con otros ojos: no como dibujos literales del planeta, sino como sofisticadas herramientas científicas que conectan matemáticas, física y geografía.

Updates and details can be found at

Updates and details can be found at  Ver el vídeo:

Ver el vídeo: